Cocaine is a central nervous stimulant drug made from the coco leaf primarily made in Columbia, Peru and Bolivia. The cocaine extraction process is complex and involves heating, then cooling the leaves. Alcohol is then added and distilled off to create the most pure alkaloid form. U.S. pharmaceutical companies use cocaine for legal medicinal use as a topical anesthetic. In this article you’ll learn the difference between crack and power cocaine and how to get your sentence reduced.

However, most cocaine is produced for illegal use. Cocaine is usually exported from South America in power form. The chemical name for powder is cocaine hydrochloride. It has a high boiling point and therefore, cannot be smoked. Traditionally, it’s snorted.

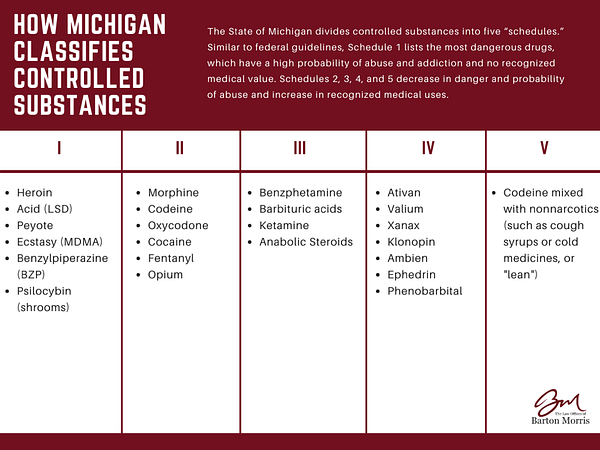

The Federal Government has classified Cocaine as a Schedule II controlled substance, which means the government deems that it has high potential for abuse but also has accepted medical use in treatment.

Facing a cocaine charge? Unhappy with your current attorney? Request a free consultation now.

What is “freebasing”?

In the 1970s, freebasing cocaine became the popular way to receive a more intense and immediate high. The process of freebasing involved removing the salt (hydrochloride) from the powder, thereby allowing the boiling point to be lowered and more easily smoked, which affected the Central Nervous System (CNS) quickly and intensely. This method used a lot of powder cocaine and therefore, it was expensive.

Freebasing involved heating powder cocaine and mixing it with ether and ammonia. After it cools and dries, the cocaine is smokeable. The problem was that because ether is highly flammable and users could not wait to smoke the end product.

Richard Pryor had a lot of money and was a known cocaine user. Therefore, he preferred freebasing. On June 9, 1980, Richard Pryor could not wait for the product to dry and when he went to light it, he caused an explosion and burned over half his body (it was also said that he tried to commit suicide).

What is crack cocaine?

In the 80s, a less dangerous form of cocaine freebase was created, called crack cocaine. The process also removed the salt from the powder, except this was done by mixing it with baking soda and then heating it. After it cools, it hardens into rocks. Crack cocaine is much cheaper, which aided its popularity.

A perceived “crack epidemic” resulted in the mid 1980s, which prompted congressional hearings during the summer of 1986. The result of the hearings created the following findings:

- Crack cocaine is much more addictive than powered,

- Crack produced psychological effects that were worse than powder,

- Crack attracted users that could not afford powder particularly young people, and

- Crack cocaine led to more crime.

Because of these findings, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 created very stiff penalties for crack cocaine, including mandatory minimum sentences for simple possession of crack cocaine. The sentencing disparity for dealing crack and powder cocaine was 100 to 1. For example, the possession of 2 ounces of crack cocaine carried a 10-year mandatory minimum jail sentence, compared to 179 ounces of powder cocaine for the same penalty.

Racial Disparity in Crack Epidemic

Since then, the Federal Bureau of Prisons began to have budget and overcrowding problems. Minorities, especially African Americans, were disproportionately incarcerated. More that 80 percent of federal prisons serving crack cocaine sentences were black.

The tough sentencing scheme wasn’t working. It was acknowledged that the 100 to 1 ratio was unjustified and without empirical support. It was deemed “one of the most notorious symbols of racial discrimination in the modern criminal justice system,” by Senator Patrick Leahy, Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

In August 2010, President Barack Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 to “restore fairness to Federal cocaine sentencing“ laws. The Act reduced the federal crack vs. powder disparity from 100 to 1 to 18 to 1. The new law was also made to apply retroactively, where persons under the old law could get re-sentenced and their jail sentences significantly reduced.

Minimum Prison Sentences for Cocaine Offenders

Mandatory minimum prison sentences still exist. A federal conviction for possession of cocaine with the intent to distribute a minimum of 28 grams of crack, or 500 grams of powder carries a minimum of five (5) years in prison.

The sentence increases if the offense involves a firearm, violence, or injury to another and if the offender has a prior criminal record. Lesser jail sentences are given to offenders who deal in smaller amounts of crack and powder cocaine.

Facing a cocaine charge? Unhappy with your current attorney? Request a free consultation now.

Chemistry of Cocaine

The chemistry of cocaine is important to note. Cocaine is cocaine, whether it begins as a salt (cocaine hydrochloride or powder) or a base (crack cocaine). Human bodies remove the salt molecule to convert the cocaine to a base, which allows it to get to the receptor. That is why smoking it is faster, because the base is already there. Therefore, many still see the 18 to 1 disparity as unfair and prejudicial.

Significantly, there are no other drugs that have this type of disparity based upon the manner in which it is ingested. Heroin and marijuana may be introduced into the body in various ways which produce very different speeds of effect but there is no difference in sentencing.

Reducing Jail Sentences for Non-Violent Offenders

In 2014, the United States Sentencing Commission recommended to further reduce jail sentences for all non-violent controlled substance offenders. Attorney General Eric Holder supports the recommendation and the new law took effect in November 2014. The District United States Attorneys have already enacted policies to allow lesser penalties for federal defendants convicted of non-violent controlled substance offenses.

The State of Michigan’s drug laws do not have mandatory minimums or differentiate between powder and crack cocaine like federal law does. State law makes a distinction in penalty with offenses involving under 50 grams of cocaine, between 50 and 450 grams (penalty starting at 12 months jail), between 450 and 1000 grams (starting at 36 months in prison), or above 1000 grams.

Facing a cocaine charge? Unhappy with your current attorney? Request a free consultation now.